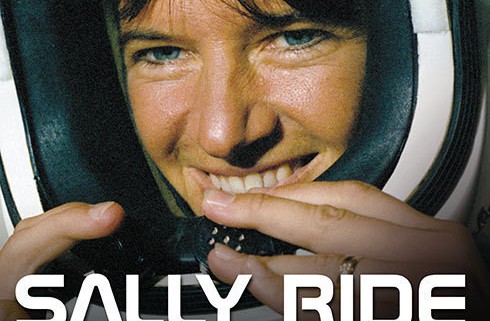

Sally Ride and the Quest for Social Space

by Mary E. Hunt

from Feminist Studies in Religion

Lest anyone think that LGBTIQ rights were accomplished when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of marriage equality, I beg to differ. Read Lynn Sherr’s marvelous biography Sally Ride: American’s First Woman in Space for a reality check. This is a marvelously written, highly informative, and deeply touching story of an American hero who changed forever what an astronaut looks like. She also lived the consequences of heterosexism.

I found the story riveting. I expected a fairly straight forward, as it were, rendering of Sally Ride’s remarkable life with a concluding chapter about her untimely death in 2012 at the age of sixty-one. Instead, I found a skillfully and tastefully written biography that traced the trajectory of a smart young tennis player who chose physics over the courts and became the first American women in space. Only her obituary revealed that Tam O’Shaughnessy, her partner of twenty-seven years, survived her. Yet the thread of Sally’s love for women runs throughout her life.

Sally was a hero whose brilliance and focused work helped her to “reach for the stars” as she advised the rest of us to do. So why was her loving relationship with a fine woman something to cover with a space blanket? It was not as if they were mass murderers. In our heterosexist society being out is still a major risk factor for dis-ease.

Sally Ride followed her NASA missions with a substantive career as a scientist. She distinguished herself as part of the investigatory teams that figured out why two space flights failed, killing the astronauts aboard, and what NASA needed to do about it. She became the founder of a company that promotes STEM for girls. Along the way, she had a woman lover in college, dated a few men, and even married one. Lynn Sherr, a friend of Sally’s, makes clear that the brave explorer simply never had the intensity with men that she mustered for women. Many women know the feeling.

By all reports, Sally was an extremely private person who chose to keep her personal life out of public view. That was her call and I respect it. But I still found myself weeping in despair. Decades of struggle on virtually every front to make LGBTIQ lives matter, and this is the best we could do for Sally Ride? What about poor women, women of color, women who have none of her social capital? There is work to do and lots of it to make the many ways people love safe and acceptable.

What drew me up short at the end of the book was that Sally Ride chose to make clear and calculated choices about her personal life because society’s homohatred is still so virulent. She judged that the cost of being out was higher than she wished to pay. What an indictment of our society.

Sally Ride had become a “public person” due to her fame as an astronaut. That is not an easy road, especially for someone who is generally introverted. Sally had the integrity to use her fame to help girls and women fulfill their dreams. That she could not let her long term love relationship be part of the example she set, a dimension of the role model she knew she was, remains a deep sadness for me. I do not blame her. I simply note the unfinished agenda that the rest of us have inherited.

Sally was spooked by what happened to her good friend, tennis great Billie Jean King, who was outed in a palimony case in 1981. Billie Jean was closeted because she felt the pressure as the women’s tennis tour was just starting up. Having open lesbians in leadership would not have been advantageous. Billie Jean paid dearly in many ways, especially financially.

Sally watched that debacle close up and reasoned that she, too, would pay a high price. NASA would surely have made a different choice for the “first” woman had Sally been out. Decades later, corporate support for Sally Ride Science, the company that she and colleagues set up to “make science cool” for young women hung in the balance. Ironically, President Barack Obama awarded both Sally and Billie Jean Presidential Medals of Freedom. Still, progress on LGBTIQ acceptance has been minimal if icons live with such fears. I repeat, what about other less privileged people?

It would be easy to write off Sally Ride’s choice to be closeted as one person’s idiosyncrasies, or as something that her very privilege could buy. But what pains me is that Sally’s is not a unique story. Many people live with the same fears, the same pressures on intimate relationships, the same lack of transparency with all the psychological, physical, and spiritual costs that go with it.

I began to think about the dozens of women I know who are Sally’s age (which is my age) and older, who will go to their graves never having uttered the truth of their love. I mourn that loss. Whether they are scholars, members of Congress, house cleaners, health care workers, artists, nuns, ministers, athletes, waitresses, IT staff, teachers, stay at home moms, whatever their situation, many do not discuss their relationships with women because they are afraid of the consequences. Their terror at being found out, the huge price tag on their safety and well being defies excuses.

Race, age, national origin, economic resources all play a part in such decisions. Blaming the victim is never appropriate. But if someone of Sally Ride’s stature felt pressure, how much more do other women feel it.

What are we doing about the fact that we can visit outer space but we cannot create enough social space to accommodate the range of ways people love? Abolishing heterosexism thus creating space for love is as fitting a way to honor Sally Ride’s memory as naming a ship or a lunar impact site after her. Solidarity not outing is the obvious strategy. One doesn’t have to be a lesbian or a woman, whatever those words mean now, to participate.