Follow Up to WATERtea

“What White Feminists Need to Know about Intersectionality”

with Chanequa Walker-Barnes

Tuesday, June 8, 2021 at 2pm ET

The audio recording is available here and the video recording is available here.

Mary E. Hunt, Introduction

Welcome one and all to WATER’s June 8, 2021 tea with Dr. Chanequa Walker-Barnes. Happy summer in the northern hemisphere, winter in the southern hemisphere, and best wishes for LGBTQIA+ Pride month.

WATER programs are aimed at supporting and igniting social change. Whether in theology, ethics, or ritual, WATER’s efforts are geared to bring together solid academic/scholarly data with the activist commitments of our Alliance. We are delighted to welcome Dr. Chanequa Walker-Barnes to our table because she does just that—bringing a wealth of studies and experience both in religion and psychology to the work of social transformation, especially anti-racism and anti-sexism. With gratitude, I offer our speaker a warm welcome.

Chanequa Walker-Barnes, Ph.D., is a licensed clinical psychologist as well as a public theologian. She is an ecumenical minister whose work focuses on identifying and healing the individual and societal legacies of racial and gender oppression. Those will be part of our focus today as we look at “What White Feminists Need to Know about Intersectionality.”

She writes of herself, “Beyond the classroom, Dr. Chanequa Walker-Barnes spends most of her professional energy writing and ministering to clergy and faith-based activists. Her faith has been shaped by Methodist, Baptist, and evangelical social justice communities as well as by Buddhism and Islam. She was ordained by an independent fellowship that holds incarnational theology, community engagement, social justice, and prophetic witness as its core values. She currently serves as Associate Professor of Practical Theology at Mercer University School of Theology.”

I note the delight with which it was announced recently that she has become part of the faculty of Columbia Theological Seminary where she will be professor of practical theology and pastoral counseling. She belongs to the American Psychological Association and the Association of Practical Theology, and she is on the editorial board of the Journal for Pastoral Theology.

You may have seen her names associated with a powerful piece, “Prayer of a Weary Black Woman,” which caused some right-wing pundits to accuse her of racism – what? She responded with a Tweet that should have stopped them cold: “The folks critiquing have clearly never read Psalms (other than 23 & 100). Cause then they’d recognize what it’s modeled after.” It did not stop the torrent of opposition. Some continue to bray and moan, but her work shines as you know if you have read the chapter we distributed, “Racism is not a Stand-Alone Issue” from her book I Bring the Voices of My People: A Womanist Vision for Racial Reconciliation (2019).

Dr. Walker-Barnes is also the author of Too Heavy a Yoke: Black Women and the Burden of Strength (2014).

Here is WATER’s blurb for I Bring the Voices of My People: A Womanist Vision for Racial Reconciliation (Eerdmans, 2019) as featured on What We’re Reading:

“This is an important read for people working to overcome racism and white supremacy. Dr. Walker-Barnes makes clear in chapters entitled ‘Racism is Not about Feelings or Friendship’ and ‘Racism in not a Stand-Alone Issue’ that racism is a matter of power which needs to be dismantled. This analysis is not intended to make white people feel the least bit comfortable. Rather, it is direct call to forget ‘cheap grace’ reconciliation and warm, fuzzy feelings and get on with the business of making substantive structural changes. Amen.”

So we invited you, Dr. Walker-Barnes, to bring your wisdom and your grace to this WATERtea. Thank you for accepting our invitation. We look forward to your words.

Dr. Chanequa Walker-Barnes

Slide images are by Dr. Walker-Barnes; notes are by WATER Staff

The word “intersectionality” is often used inaccurately

- Often by White women and LGBTQ people who learned the word through activism

- It resonates but is misunderstood

- Doesn’t adhere to original meaning and intent

- Often thought of as synonymous with multiplicity:

- The “multiple layers” of our identity, e.g. gender, race, language, ability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, etc.

- To say it is about how we bring those different components of our identity to bear and how they influence each other is multiplicity

- Identities are multi-layered and depend on context; sometimes one part of our identity will come to the foreground more than others

- We’ll pull on specific parts of our identity or one part will impact the other parts depending on where we are/who we are with

- Intersectionality goes a step further – not just layers but how those layers interact with issues of power, privilege, and oppression

- Intersectionality is keenly concerned with people who exist at the intersection of multiple forms of oppression, and the intersection of oppression and privilege

- g. Black women experience both racism and sexism, and the intersection of those two -isms creates a unique experience that isn’t accounted for by racism or sexism alone, but by being both Black and a woman

- The same goes for people with disabilities, LGBTQIA people, people who are poor, etc.

- When living at the intersection of multiple forms of oppression, one is likely to experience something different than someone who only experiences one form or who lives at a different intersection

- Intersectionality says we miss how oppression really works when we don’t pay attention to those specific intersections.

- “Whataboutism” – e.g. in the classroom, when a person of color is talking about their experience of racism and then a white student says, “You can’t talk about racism by itself; you also have to talk about homophobia and transphobia, too.”

- This decenters the experiences of people of color

- Rhetorical strategy used to defuse racism in the name of intersectionality

- This misuse of intersectionality weaponizes it against POC, especially when it happens towards women of color

- Leads to the decentering of Black women and women of color

- Intersectionality is a theory and analytical tool crafted out of the experiences specifically of Black women and other women of color

- People will use “intersectionality” without understanding the genealogy and attentiveness to its purpose, without mentioning women of color, rendering them invisible in a theory that was meant to center them

- Intersectionality doesn’t always have to be applied to women of color, but those groups need to be understood well in order to use the intersectionality framework appropriately

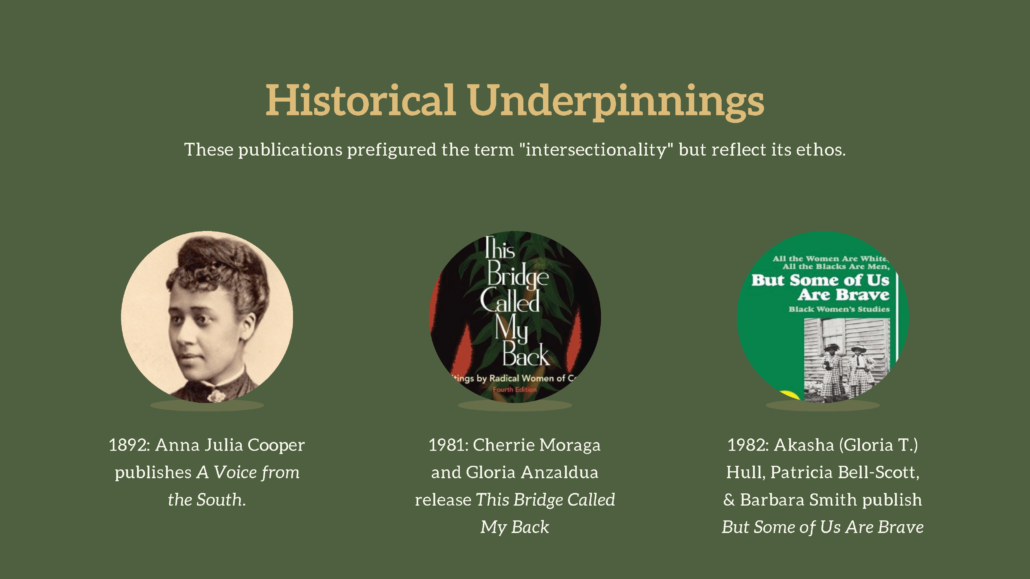

Intersectionality is a relatively new term (about 30 years old) but reflects the approaches Black women have been using in activism, organizing, and scholarship for at least a century.

Foundational texts/precursors:

- Anna Julia Cooper’s A Voice from the South, 1892

- Born into slavery, and once emancipated, got her degree(s) and PhD

- 4th Black woman in the US who earned a PhD

- In A Voice from the South, articulated the unique role Black women played in the civil rights movement of the time, same time as W.E.B. DuBois

- Because Black women experience both racism and sexism, have unique vantage point to watch goings-on of US

- Find solutions/have perspectives that Black men and White abolitionists couldn’t anticipate/see

- Born into slavery, and once emancipated, got her degree(s) and PhD

- This Bridge Called My Back edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua, 1981

- Essays by women of color across the spectrum in the US: Black, Chicano, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian

- Came about when women of color made an exodus from a feminist organization after the civil rights movement and during the women’s rights movement

- WOC found themselves frustrated by Black men dismissing their claims of sexism, saying there wasn’t time for that/it was divisive/focus only on racism

- They had a similar experience in White feminist organizations, being told they can’t focus on race and can only work on issues that affect all women universally

- Because WOC’s experiences were not being heard, they wrote this compilation of academic theory, poetry, and memoir

- All the Women are White, All the Blacks are Men, But Some of Us are Brave by Akasha (Gloria T.) Hull, Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith in 1982

- Gender issues have been defined by White women; racial issues have been defined by Black women: that leaves Black women out of the equation because there are things unique to Black women only they can articulate

- First book published in Black Women’s Studies

- Womanist theologians (for example, Jacquelyn Grant) were present in these conversations from the beginning

Signal text in both This Bridge Called My Back and Some of Us are Brave: Combahee River Collective in April 1977

- By a group of Black lesbian women who were talking about the experiences they had in civil rights and women’s rights movements

- “It was our experience and disillusionment within these liberation movements, as well as experience on the periphery of the white male left, that led to the need to develop a politics that was antiracist, unlike those of white women, and antisexist, unlike those of Black and white men.”

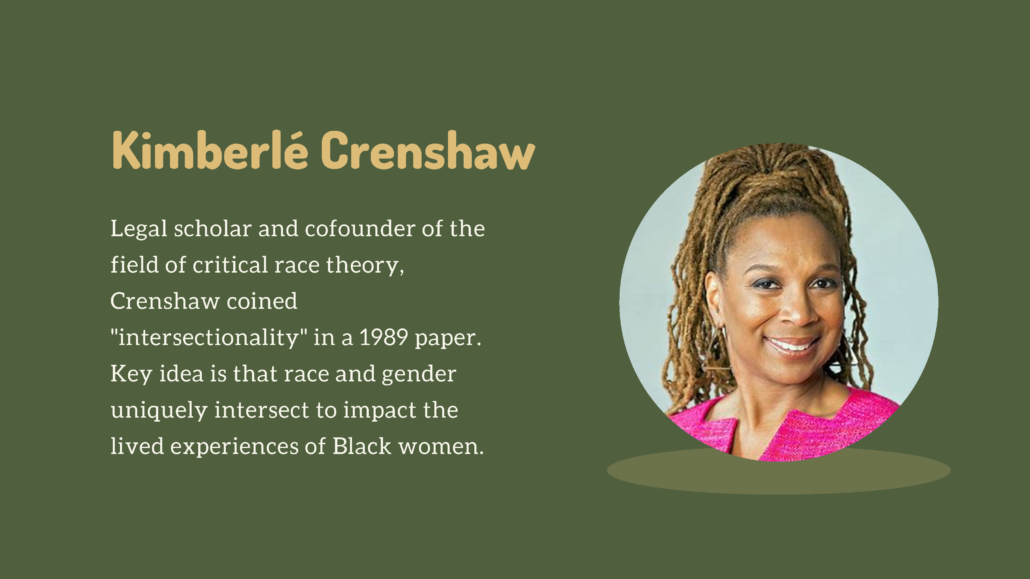

Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” in 1989

- One of the organizers of the Critical Race workshop at Harvard in the 80s where they developed critical race theory

- Published article using the term “intersectionality”

- Gave an example of how unique role of Black women is overlooked in justice movements: in LA, trying to get data on number of domestic violence incidents that involved Black women

- Approached law enforcement office, asking for this data but they refused to give the data that would identify racial and gender identities

- Two opponents:

- Male-led racial justice activists didn’t want the data to indict Black men, making it look like they were the disproportionate perpetrators

- White feminist groups doing domestic violence work didn’t want to give the idea that only Black women experience intimate partner violence as they worked to diffuse the idea that domestic violence only happens among people of color and poor people

- Marginalized groups with competing interests leave Black women in a position that “resisted telling,” rendering them invisible

- For Black women, there are some elements of their experience that are going to be similar to those of women in general, and there are elements that are going to be in common with Blackness in general → AND experiences specific to being Black women, experiences over and beyond sexism alone and racism alone

Intersectionality’s Key Concerns

- Concerned with identity and inequality: no separation of the two

- How identity is bound up in privilege and oppression in different ways

- Can experience multiple forms of privilege while also experiencing multiple forms of oppression

- At any given time, those different forms of oppression and privilege feed off each other and compete with each other

- Concerned with justice

- Use intersectionality for the cause of justice and equity/equality

- Focused on Black women and women of color

- In an extremely patriarchal and racist/White supremacist world, Black women and women of color are at the bottom

- Because of that placement, they have a different vantage point on oppression and privilege

- If justice work is geared towards the most marginalized groups (especially taking into account sexuality, poverty, disability, etc.), it lifts up everyone

- In an extremely patriarchal and racist/White supremacist world, Black women and women of color are at the bottom

- Find resource guides on her website, at https://drchanequa.com/resource-guides, on racism, intersectionality, and racial justice

Use of intersectionality in her work, particularly in I Bring the Voices of My People

- Spent about ten years in the Christian racial reconciliation movement

- Largely in evangelical social justice organizations: Christian Community Development Association, Sojourners, etc.

- Found that when talking about reconciliation, the perspectives often centered the experience of young Black men and occasionally Latinx or Indigenous men, and sometimes White women

- Black women left out of the conversation and that shapes the movement in powerful, negative ways

- Reconciliation is centered on relationships: e.g. at these conferences, Black man and White man on stage, “hugging it out” like everything is fixed now → more relationships, more diversity “solves all the racial problems,” as if people just being in closer proximity to each other is going to fix the whole problem

- When brought this up to her relatives, the women – Southerners, descendants of slaves, working class – all start laughing because they have all been domestic workers, nursing home caretakers, etc. and they’ve spent a lot of time in relationship with and caring for White people

- Women of color know instinctively that relationship and proximity do not solve the problem of racism, and sometimes it makes it worse because proximity increases vulnerability to racism in the interpersonal sphere

- By excluding the voices of Black women, Latinx women, Indigenous women, Asian women, the racial reconciliation movement missed this whole idea that relationships alone are insufficient to make social change

- What we’re talking about are patterns, systems, and ideologies that impact every level, including the politics of beauty which were never talked about

- Perspectives of women help to enrich our understandings of race

- Perspectives of women of color help to see nuance of race

- Perspectives of White women help see some things, too

- During backlash against “Prayer of a Weary Black Woman,” published in the book A Rhythm of Prayer: A Collection of Meditations for Renewal edited by Sarah Bessey, both Bessey and Walker-Barnes got pushback, but in slightly different ways:

- Pushback for Walker-Barnes: what that black woman did pushback for Bessey: what that White woman allowed that black woman to do

- That tells us something profound about how patriarchy and racism work, and can take that to learn how to get to a just world

Q and A / Discussion

Comment: Racism is not about feelings or friendship but the hard work that goes into the dismantling of power, and those of us who are White live in a very different place of privilege than those who are Black and other people of color. Thank you for saying this without apology.

Q: In reaching my 80s, ageism has entered into my consciousness more than ever before, and I wondered if you have spoken to the issue of ageism in the context of your study, how it may affect Black women and women of color differently than White women?- A: I’ve focused almost solely on race and gender in this book, but that’s an interesting thing to observe, how women and women’s authority – especially spiritual authority – and experiences change over their lifetime as they get older

- Can already/easily see a difference in how women and men age, especially witnessed in Hollywood

Q: Appreciative of your educational work, and wondered if you find that responses to these ideas differ depending on the audience?

- A: Varies by race and gender as well as by ideology

- Black audiences’ response: “Well, no duh”

- From women of color, they experience relief that their experience has been named, something they knew but couldn’t articulate

- From White audiences, it varies on the ideology

- Can have tremendous pushback and defensiveness

- For others, when addresses “what to do with whiteness,” many are open to that because they are given something tangible to do

- Look at own culture and how it shaped you to be White – something for White people to hold onto

- Troubling in a good way, something to wrestle with

Q: In coming across queer advocacy and anti-racism work, often the question from one group to the other: your focus on queer folks is taking time away from racism, and vice versa, your focus on racism is taking time away from queer folks

- A: This is where competing interests comes in, out of a mentality of scarcity which is a capitalist idea

- The way we have seen the civil rights and women’s rights movements work in meting out justice to certain groups at the expense of others

- Only so much to go around, so it has to be fought over

- That serves the interests of White supremacist patriarchy

- Have to learn to provide space for all marginalized groups and intersections

- In organizing with groups of women of color, provide space for every ethnic group to meet individually to talk about individual issues, then come back as a group to learn from each other and share the distinctions, similarities, and where interests might rub up against one another

- Finds where can join together and create coalitions

- In organizing with groups of women of color, provide space for every ethnic group to meet individually to talk about individual issues, then come back as a group to learn from each other and share the distinctions, similarities, and where interests might rub up against one another

- The way we have seen the civil rights and women’s rights movements work in meting out justice to certain groups at the expense of others

Q: As a teacher at a small liberal arts college, teaching cultural and social theory, I’ve struggled in conflating intersectionality and multiplicity – how do I explain the difference to my students?

- A: Resources to look into:

- Vivian May’s Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries

- Gets into the common misunderstandings

- Kimberlé Crenshaw’s TEDtalk, “The urgency of intersectionality”

- Vivian May’s Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries

Q: Predominantly White organizations like WATER try to do anti-racism work by partnering with Black-led groups rather than expecting Black women to come to WATER, though they are more than welcome. What is your view of these approaches in terms of resource sharing and working collegially? It isn’t an either/or but a both/and: don’t want to put the burden on Black women colleagues to explain their experience to us

- A: Nothing wrong with diversifying organizations, but it’s difficult, and there’s this element of resonance that’s often missing

- Something evoked only when there is an (unknown) critical mass gathered together, observed in Black spaces

- Can’t take that with us, it’s only present when there are large enough numbers gathered

- Code-switching: not always conscious because when in predominantly White contexts, can’t get that thing that brings out that part of my culture, but when in a space full of Black women, that thing is able to be accessed

- Thus, the advantage of going to groups led by Black women and women of color, and there’s reason for women of color to go to each other’s spaces

Q: How to address how poor White people are often made invisible in academic conversation and White women are invisible-ized in prison justice/carceral work?

- A: Poor White people need to be able to analyze their complicity in the project of Whiteness and name their class oppression

- Figure out how they have often participated in and double-downed on the project of Whiteness as a way to deal with class oppression

- There’s a lot of self-hatred among poor White people, and they haven’t had a way to name that, e.g. “White trash” and the term’s role in White supremacy

- Often see poor White people take the side of wealthy Whites

- Belief that they can transcend poverty by adhering to White privilege

- Find a way to articulate something different, and the place where this happens: empowering poor and working-class people to lead more → these conversations happen when poor people of different races labor together, but then poor White people get a taste of privilege and leave behind everything else

- Hard time with J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy because gets to a point of blaming poor White people and doesn’t do class analysis of how poor White people are used to uphold the system

- Need to develop critical consciousness or else the White elite will always be able co-opt poor White people to make up the base of their hatred and hostility

- Look at how labor organizers have been able to do that work as one model

Q: Quoting from your book: “The critical issue for White Christians is not how they embody their humanity when the legal system support justice, but how they do it when it does not.” You describe this in terms of the South African apartheid struggles and the eventual conviction of de Kock, the head of the police who claimed he was just following the law and then was lauded later when he did some good things following the law once it changed. Would you say more about this as it has so many implications in other struggles, in BLM, even within churches?

- A: Part of the way whiteness has been framed in this country is that a critical component is following social norms – it’s how you prove your whiteness, by adhering to White social norms.

- Base one’s social ethics on what the law, authority, and social norms say

- When the ethos was on the side of police, people were overwhelmingly on the side of police, but that changed this past year when it became hip to protest and be against police, but nothing has really changed, it’s just where the social norms are currently

- White people will always go back to life-as-normal until they start to articulate a sustainable opposition to injustice and a sustainable pro-justice orientation → especially one that requires them to break the rules

- Women who see the system as wrong but will never break the rules because following the rules makes you a good person/Christian/woman

- Fear that if right-wing were to have its way and win, most White Americans will just go along with it because they’ll do whatever the system tells them to do

Q: Any further feedback from “Prayer of a Weary Black Woman” – what you thought you would get and what you got?

- A: Backlash was unexpected since success of the book was unexpected

- In this political climate with people cherry picking issues to incite race war, and because of language used, being a Black woman, and location at Mercer University (and its history of splitting from Georgia Baptist Convention after giving benefits to domestic partners) made perfect combination to be a target

- Fear for safety of family, temporarily moved to hotel because of concerns about doxing and violence → adjusting to new normal; now constantly aware of privacy and safety

- Tool of White supremacy is surveillance

- The right is engaging in this all over the place as a tactic of intimidation

- Safety and privacy balanced with still doing the work

- The prayer has sparked incredible opportunities for dialogue

- What meant to harm might actually work out for good, as book sales skyrocketed

- Think of racism as an accident, but it’s not → people actively work to make the world this way, so it gives a people a chance to see the intentionality, to sharpen to it

- Tool of White supremacy is surveillance

Comment: Basis of “Prayer of a Weary Black Woman” in Imprecatory Psalms (mainly Psalms 69 and 109, but includes 5, 6, 11, 12, 35, 37, 40, 52, 54, 56, 57, 58, 59, 79, 83, 94, 137, 139 and 143) – hadn’t read those/forgot about them; your prayer is on solid theological ground

- Response: Those psalms keep me grounded; some of them are really harsh.

Q: How do you see the relationship between evangelical Christianity and the rise of the Trump politics?

- A: Emergence of the Trump phenomenon and the Tea Party before him reaffirmed deepest suspicion that racism wasn’t gone, had just gone underground because, again, it wasn’t popular

- But never expected we’d get here

- Fascinated and disturbed by White students who say they can’t talk to their parents anymore because they’ve fallen for the Trump conspiracies

- Christianity is the culprit – is too often the culprit of atrocities – and causes wrestling with being a part of this religion

- “What does it mean for my own walk?”

- Can’t write it off as just one element – it’s the whole thing

- Those with justice orientations are the outliers

- Embarrassing to be called a Christian

- Given hope by the knowledge that Jesus knew how much we were going to mess it up, and he came anyways and still loved/s us

Mary E. Hunt, Closing

Thanks again to our speaker, Dr. Chanequa Walker-Barnes. We are adjourned for today with gratitude to all and wishing you strength in the struggle to deal with White supremacy that surrounds us.

Resources

- Chanequa Walker-Barnes’ books:

- I Bring the Voices of my People: A Womanist Vision for Racial Reconciliation

- Too Heavy a Yoke: Black Women and the Burden of Strength

- “Prayer of a Weary Black Woman” in A Rhythm of Prayer: A Collection of Meditations for Renewal (Convergent Books, 2021)

- Vivian May’s Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries

- Kimberlé Crenshaw’s TEDtalk, “The urgency of intersectionality”

- Heather McGee’s The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together

Below is a list of alternatives to purchasing these books through Amazon, recommended by the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice:

- IndieBound or Bookshop—support your local bookstores

- ThriftBooks—provides a range of used copies

- BetterWorldBooks—supports global literacy and carries both new and used books

- Libro—audiobooks from independent bookstores

- Gave an example of how unique role of Black women is overlooked in justice movements: in LA, trying to get data on number of domestic violence incidents that involved Black women